Alumni Update: Philip Stokes, PhD

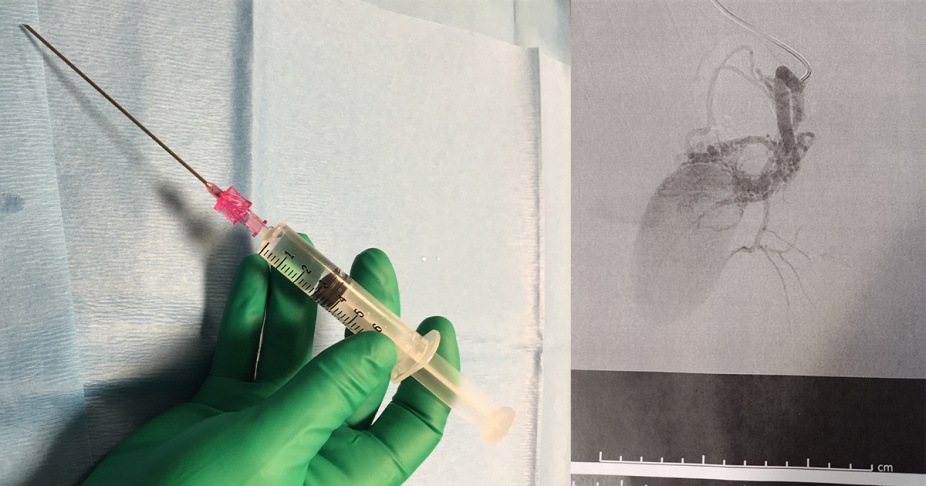

(Left) A Seldinger needle, used for arterial injections. (Right) Phil’s Twinkie-sized hodgepodge of blood vessels known as arteriovenous malformation (AVM).

Preface by the Associate Chair

Typically our newsletters focus on science and student activities in the Department. We asked Phil Stokes, President of the Geology Alumni Advisory Board (GAAB) to submit a contribution to this issue, and he gives us a light-hearted story about a health crisis that he's been dealing with. We hope this provides some chuckles (and education about a serious medical condition) amidst the ongoing pandemic. - Greg Valentine

Phil Stokes at Fall Brook Falls in Geneseo

Philip J. Stokes, PhD | Executive Director

Hamburg Natural History Society/Penn Dixie

(GAAB Chair)

Hello again to my friends and colleagues! The past year has been a struggle as many of us lost our health and loved ones to a deadly new disease. It has been challenging to find solace in hardship, but I’d like to share my story of loss – of dignity, mostly – in the hopes that you will find your silver lining among the clouds that hang above us. Disclaimer: this tale is not for the squeamish.

One year ago, just as the pandemic was beginning, I was diagnosed with a rare condition known as arteriovenous malformation (AVM). The National Organization for Rare Disorders – an interesting group to follow on social media – defines AVM as a “vascular lesion that is a tangle of vessels of varying sizes in which there is one or more direct connections between the arterial and venous circulations.” Essentially, my blood vessels went haywire and tried to kill me.

As a rare disease, AVM has an incidence of about 10 per 100,000 people; roughly 33,000 people in the U.S. live with it every day – many of them unknowingly. Unfortunately, AVMs have a rupture rate of about 5%; rupture usually results in death or serious, permanent disability. If you've ever heard of a child or otherwise healthy person unexpectedly dying from a brain hemorrhage, it was probably due to AVM.

My AVM was found in my pelvis. My doctor suspects that it was present at birth, growing along with me like a parasitic twin. In fact, when my AVM was first detected it was not clear what was going on. Bloodwork and initial radiographic imaging was inconclusive. When my doctor sat me down to review the findings, I told him I was hoping for a diagnosis of ‘parasitic twin’ so I could potentially make it into medical journals. I mean, who wouldn’t want that story to tell at holiday dinners? Alas, my doctor laughed and referred me for more testing.

My AVM is large, quite complex, and required a number of highly specialized procedures to treat. Each procedure involved conscious sedation while blood vessels were repaired from the inside -- a process called coil embolization. I was partially awake during surgery, which took place locally. In one procedure, my doctor initiated the operation through my brachial artery in my arm; in others, the iliac in my groin.

On surgery days, I mostly had the hospital to myself. Given the pandemic, all nonessential surgeries were canceled and visitors were barred. It was a ghost town (hospital?) with so few people on the floor. To my benefit, the few remaining patients were vastly outnumbered by staff. There were no delays or waits. Minus the threat of Covid-19, it was ideal.

With so little going on, scheduling was a breeze. My doctor, an experienced and locally well-known radiologist, was eager to treat my condition as quickly as possible. We scheduled procedures roughly two weeks apart from each other to give my body time to heal and expel the radioactive dye used to observe my blood vessels. I had a total of six procedures; some were not successful, but we kept trying.

When I called the hospital to schedule my final procedure, the office staff asked "Which department?" I replied "Cardiology for AVM embolization." Before I could provide my name, they interjected "Oh! You're the butt needle guy!"

The staff was referring to the embolization needle the doctor occasionally plunged into my butt. The needle, an extremely oversized version of your standard hollow hypodermic needle, was used to inject titanium coils, catheters, and coagulants directly into the bloodstream. Though I may have been delirious, it appeared about as thick around as a pencil. Confirming all of my fears, the first time my doctor jammed it in, it burned like the dickens. I remember growling, like a doped-up barbarian, at the anesthesiologist. “GAHHHH…I CAN FEEL IT!”

As more drugs were delivered, I grappled with a new psychological challenge. I had prepared myself for the big picture – my own mortality – but failed to anticipate this new trauma. “Why didn’t my doctor warn me about his giant, horrible needle?” I wondered. “Did he think I would bail?” Feeling dizzy, my thoughts traveled to Mirkwood Forest from The Hobbit. My doctor became Bilbo Baggins, and Sting was his sword. I empathized with the evil spiders and knew how they felt when they were stabbed by Bilbo in the abdomen. It all made sense.

Luckily, it was not long before I was numb and ready for my doctor’s second attempt at the danger zone. He went to work with the needle as I tried to keep my eyes open to follow what he was doing. I recall a parade of doctors and resident physicians visiting the operating room to observe how my rare condition was treated. Through the magic of a portable X-ray, they could view an image of my blood vessels while, in real time, my doctor sealed them up. For my part, I gave the audience a thumbs up when they asked how I was doing.

Thankfully, the butt needle worked and my AVM is in the equivalent of remission. I’m glad to be on the mend and hopeful that I will not need further probing. If the experience taught me anything, it’s that healthcare workers are the true heroes of science. I cannot thank my doctors and nurses enough for their efforts!

P.S. You never know who has a hidden illness. Get your Covid-19 vaccine so we can let it rip with a big Geology Department bash!

Next article: New Wells at the University at Buffalo